How I calculate insulin doses…automatically!

Any diabetic knows that diabetes management can be a pain in the ass. Let alone the injections, carrying all kinds of devices on our body and dealing with the frustrating fact that low BG levels have a special taste for important moments where we need to be at our best, there is another reason that many consider diabetes a tedium generating machine. That is: diabetes and blood glucose control require intentionality, discipline and consistency, qualities that at times we (me included) “hope” to forget in favour of the lazier way.

Filling out a decision tree requires you to document specific metrics: blood glucose measurements, any insulin injection (basal and bolus), any time you eat a meal, any time you exercise, and any stressful events. Then I look at the numbers, consider the circumstances and I just do the math. That is how diabetes gets managed.

Does that sound boring? It is.

Does that sound like something you look forward to doing? Probably not.

Is that at all necessary? It is.

Does that make a difference in the health of a type 1 diabetic? The hell it does!

I feel sad every time I hear about people that do not take their condition seriously enough or that, because they can’t make peace with it, choose to live their lives pretending that diabetes did not exist. They may seldomly look at their blood data, randomly plan their insulin doses and not care the least about the quantity and the quality of the food they eat. That is a guaranteed way to get severe health consequences in the long term.

With long term health being one’s top priority - as it should be, in my opinion -, then the guessing game with diabetes is simply not an option.

Mastering diabetes, the art of thriving with this condition instead of being enslaved by it, requires some degree of patience, commitment and discipline. The spreadsheet I use on a daily basis is the precise expression of this commitment. It is the “decision tree” that forces me to think through my recent past, adapt my meals, insulin and BG management strategy constantly.

It is also a direct and ruthless way to see how “cheat meals” and processed foods screw up our health. Once you see that that hyper processed pizza skyrocketed your BG and your insulin resistance for hours and days, it is much easier to say “ok, it is probably not a good idea to repeat that” whenever the craving arises.

My decision tree

A decision tree is nothing short of an amazing tool that can help to lower blood sugar and master the insulin process. Think of a decision tree as a super simple tool that gives you insight into exactly what is affecting your blood glucose throughout the day. It can be as simple as a piece of paper and a pen, but I prefer a spreadsheet like the one below.

Overview of my Decision Tree.

There are two main reasons I use a spreadsheet:

I can use some simple math formulas to automate the calculations of the actual and predicted carb:insulin ratios

I can have it on my phone at all times, with no need to carry any sheet of paper or pen with me.

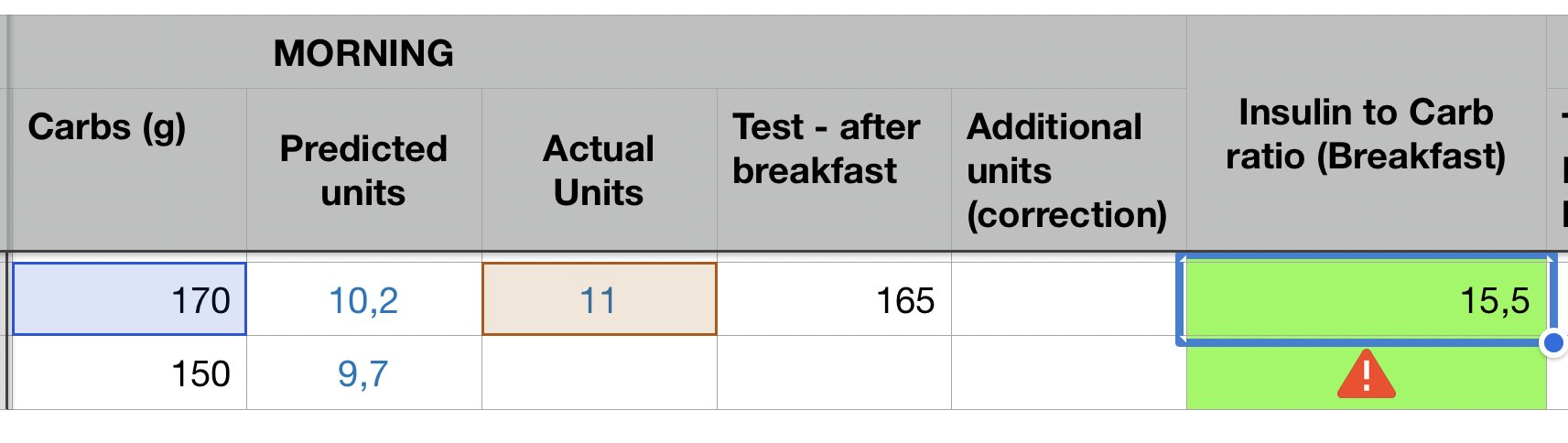

Using a spreadsheet makes the whole process a lot easier: I just log the amount of carbs and the formulas will spit out the exact amount of insulin I need based on the amount of carbs I am about to eat. Like it or not, the common saying “What gets measured gets managed” is perfectly suited for diabetes, and that is why in this spreadsheet, for each meal, I measure and log this data:

my blood glucose,

the grams of carbohydrates

the grams of fats I eat

The predicted carb:insulin ratio

The actual units of insulin I inject

The actual carb:insulin ratio

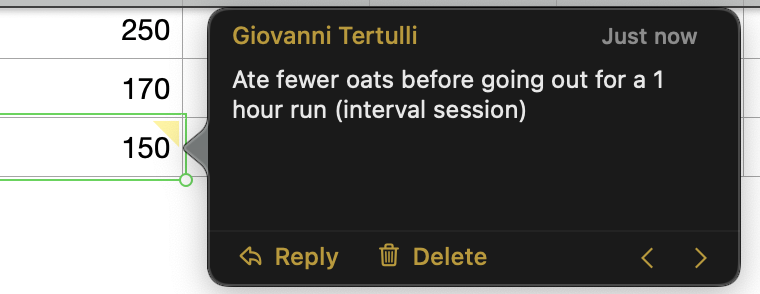

A “comment” section, where I add details such the food I ate, the amount of physical exercise I did, and so on.

All of these contribute to the computation of your insulin sensitivity, and inform your next best action.

Prerequisites for a decision tree to work

A diabetic who wants to maintain a stable and in-range blood glucose must at least know:

the amount (g) of carbohydrates of each meal

the insulin-to-carb ratio (or the grams of carbohydrates a single unit of insulin can handle, a good indication of insulin sensitivity) for a given meal the day before.

I would put the amounts of fats as mandatory too because they can significantly impair the effectiveness of insulin, but if you’re just getting started, carbohydrates are good enough for now. But how can one possibly know the exact amount of carbs and fats of a meal? Fair question! Here’s my answer: that comes with experience and with consuming a range of selected plant based green light foods that you get to know very well after some time.

I am not kidding when I tell people I know the nutrition facts of each food item in my plate! Did I actually sit down and spent hours memorizing them all? Nope! Instead, I logged my food in apps such as Cronometer for a long enough time that their nutritional info became imprinted in my head. Something else that makes the whole process much easier is to rely on a stack of simple recipes that you rotate.

Put simply: I eat 100g of oats with 1 banana, 10g chia seeds and 500g apples every morning. Since 90% of the time my breakfast doesn’t change, I literally don’t have to do any calculation or any good logging to know that the amount of macronutrients of my meal is:

My typical breakfast.

Same idea for lunch and dinner: by sticking to a range of known ingredients (whole grains and legumes), the effort and the mental load required to “learn” their facts is much lower, and it takes a fraction of the time.

After a while, you’ll develop the intuition that allows you to correctly estimate the nutritional content of a meal with no effort. Then, you just have to weight the ingredients, adjust it based on the amount and you’re good to go. This is how I know the exact carb and fat content of my usual salad bowl with chickpeas, or that of the rice and beans I eat when I am at the office, for example.

Building the decision tree

With that information, I just log the numbers and get my suggested units of insulin for any given meal, based on the meal I ate the day before.

To get the correct prediction, I compute two metrics for each meal of the day (breakfast, lunch, dinner):

the carbs:insulin ratio of the previous day meal, computed as:

(grams of carbohydrates I ate) / (units of insulin I injected)

Yesterday’s carbs:insulin ratio

the predicted units for the meal I am about to eat, computed as:

(grams of carbohydrates I am about to eat) / (carbs:insulin ratio of the day before)

Today’s adjusted units prediction.

Before a meal, I take a few seconds to estimate the amount of carbs (and fats), log the number into the “Carbs (g)” column, and the spreadsheet will kindly show me the ideal amount of predicted insulin I need based on the previous day’s insulin sensitivity for that meal. Then I decide if that amount is appropriate or it should be adapted, based on context-specific information: if I am running, I know I can reduce; if I am eating more fats or more carbs, I will have to increase it.

Interpreting the decision tree

In the example above, my “yesterday” (first line) carbs:insulin ratio was about 16 because I ate 170 grams of carbs and injected 11 units of bolus. 170/11=15.5 means that one unit of insulin handles roughly 16 grams of carbohydrates, and with this ratio I got a post-meal BG of 165.

My “today” (second line) predicted amount will take that into account! Since today I plan to eat 150 grams of carbs - 20 less than yesterday - my predicted units are 150/15.5=9.7, which I round to 10. Now, will I inject exactly the suggested 10 units? That depends. Here’s how I interpret the decision tree and my thinking process before loading the insulin pen:

Since a 15.5 ratio the day before resulted in a relatively high blood glucose level, it is likely that I need a bit more insulin to stay in range at breakfast. Probably, yesterday I should have used 12 units instead of 11. So even though my predicted units is 10, it is better to inject 11.

Other factors could affect my decision. For instance,

if today I run after breakfast, I will surely not increase the units - in fact, I might have to decrease them, because running will compensate for the “missing” insulin.

if yesterday I ate 100g of oats and today I eat 100g of apples, I will drastically decrease the units because I know from experience that 100g of apples barely affect my BG.

if today for some reason I eat a fatty breakfast (say, vegan toast with peanut butter and jelly) I will increase the units because I know that a toast with jelly, refined carbs, will spike my blood glucose. It might even be necessary to inject a few units a couple hours after the meal, because the fats contained in peanut butter can delay the spike in blood glucose.

All these things should be documented and tracked in the decision tree. I typically do that by adding a small comment on the cell explaining why I ate a different amount, the type of food or the physical activity I did before/after the meal.

Always add comments!

Additionally, every meal and every moment of the day will have a different insulin sensitivity. You should not be surprised to discover that your morning and evening carbs:insulin ratio can differ significantly. In my own experience, my decision tree has shown me that I tend to be much more insulin resistant in the evening…good to know! Since I discovered this, I have been loading my dinners calorie intake a bit less.

Master your diabetes with your own decision tree!

A decision tree is definitely one of the most powerful tools in my “mastering diabetes” strategy. Keeping track of all my numbers helps me immensely in reducing the guess work and keep my blood glucose stable. It also offers me a great overview on the evolution of my diabetes metrics allows me to better detect patterns and ask the right questions:

am I becoming more insulin sensitive?

more insulin resistant?

how did the food I ate during that 2-week vacation impact my BG levels?

how does carbs:insulin ratio behave on the days where I run?

why do I have high BG in the morning? Might have something to do with what I usually eat at dinner?

Consistency over a long period of time will help you to take more conscious decisions. After a while, your “decision tree” could grow and start to become a scary big monster of several thousands of rows like mine!

Some data from a few years ago…“Damn, that escalated quickly!”

But don’t be scared! It is not a monster at all, it is your very best friend. The bigger the tree, the better, because you have more data, more documented history to inform your diabetes management strategy.

While it may seem overwhelming at first, I guarantee you that having a simple spreadsheet on your phone will significantly reduce friction and effort. You just have to spend some time getting to know the nutrition in the foods you eat, “memorise” their carbs and fats content, and throw the numbers in the right cell. The pre-filled formulas I have shown you above will do the math for you!

Now…go and start grow your tree, it goes a long way!😁

Check out Mastering Diabetes video about Decision Trees!